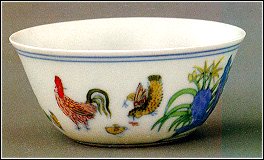

Chenghua Chicken Cup

For centuries now, scholars have written on the subject of the illustrious 'Chicken Cup' first produced during the reign of the Ming emperor Chenghua (1465-1487). Almost every book covering the subject of Chinese porcelain mentions the rare cup. It is reported that there are only fifteen known in existence, mostly in museums, and only three in private hands. Made strictly for the Imperial household, it was said that the later Ming emperor, Wanli (1573-1620), was very fond of the cup. It is also documented that a pair was known to fetch as much as the equivalent of $10000 US dollars during the end of the Ming reign. Because of the popularity, copies were produced during various reigns of the later Qing dynasty with both the current reign mark and the apocryphal (or spurious) reign mark. The latter proving problematic for centuries to the porcelain connoisseur. It was a well know fact that there were corrupt official within the Imperial Palace, and just as well known that on occasion a piece was 'smuggled' out of the Imperial kiln, rather than be destroyed, should it have a minor flaw. An alliance between the corrupt officials and the head of the kiln created an underground that channeled an occasional piece of Imperial bound porcelain to a non-imperial destination for a nice profit. Though this practice has been documented by both scholars and historians, there has yet to be an authenticated example of a Chenghua chicken cup originating from this source. This cup provides an excellent example. |